Foreword

Just as importantly, this report seeks to make the case to the Chairs and CEOs of the UK’s largest businesses – to embrace good supply chain practice, to learn from each other and to lead from the front, with clear accountability at board level. Government should require larger companies (as defined by the Companies Act) to have a named non-executive board director with clear accountability for all supply chain issues.

This report also examines the critical role that Government and the wider public sector can play in promoting best-practice throughout their own substantial supply chains, a win-win for businesses and tax payers alike.

Supply chains can be a powerful lever for wider business and societal reform, from supporting smaller suppliers to export and innovate, to making it easier for smaller firms to take on apprentices. It’s time to take full advantage and give our economy a much needed boost.

Support

Only 12% of smaller suppliers received skills and workforce support

Positive impact

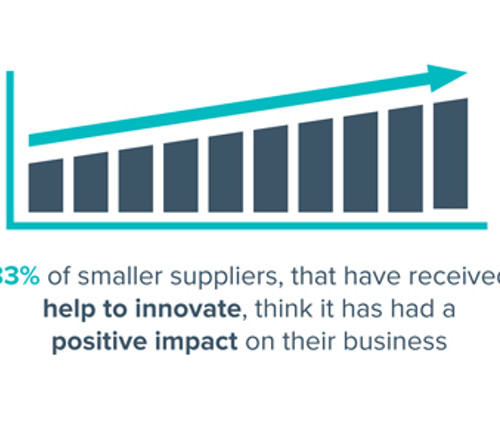

Help with supply chain innovation has a positive impact.

Who helps?

Some customers support innovation

Standards

Verified standards are high

Payment

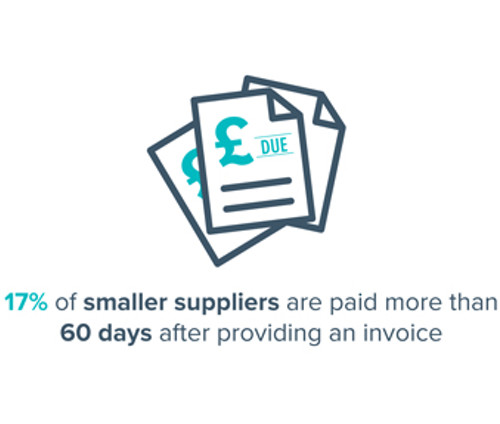

Payment is often more than 60 days after invoice

Payment terms

Payment terms have increased for many

Risks

Supply chain risks for smaller businesses

Certification

Average cost of certification

Late payment

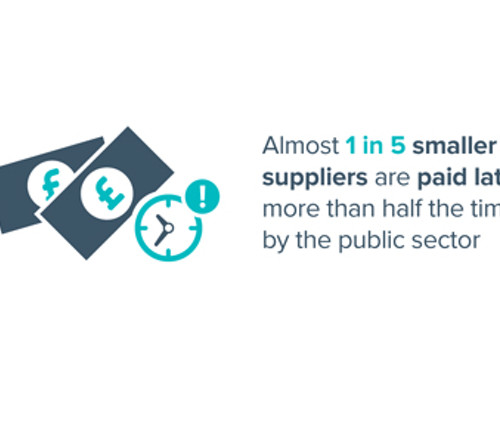

Many small suppliers are paid late

Executive summary

Healthy supply chains are critical for boosting the productivity, resilience, financial strength and efficiency of smaller and larger businesses alike, and economic growth across the UK. However, there is a lack of data and understanding about the factors that influence supplier experiences in business-to-business (B2B) and business-to-government (B2G) markets.

This report shows that in order for policy to be designed to maximise the benefits of healthy supply chains, policy makers must consider the following factors that affect the experience of small UK suppliers:

- Supplier size (sole trader, microbusiness, or larger)[1]

For example, suppliers with 11-20 employees are more likely to report higher levels of skills and innovation support from customers, compared to other size groups. And this size group is most likely to say their innovation support relates to ‘collaboration in design’, compared to other size groups which tend to cite ‘sharing of workforce expertise and time’. As suppliers grow beyond the size of a microbusiness, their payment terms tend to get worse, they are more likely to hold at least one certified standard, and tend to hold more of them (and pay more for them). - Sector in which the supplier operates

For example, smaller suppliers in the manufacturing sector tend to receive more support for innovation from their customers, compared to some other sectors. Those in manufacturing are also most likely to cite ‘collaboration in design’ as the most common type of innovation support offered, with a very strong focus on product innovation. Those in manufacturing are much more likely to experience payment terms of more than 30 days, compared to other sectors, but are more likely to be paid on time. They are also less likely to hold at least one certified standard, and tend to hold fewer of them, compared to some other sectors. However, the standards they do hold tend to come at a high cost. - Geographic market(s) covered by the supplier

Across all geographic markets, the most commonly cited benefit resulting from innovation support from customers is ‘improved reputation, credibility and profile’. However, the benefits of such innovation support get more diverse and numerous as the size of geographic market increases. - Relative size and type of customer

For example, smaller suppliers to a single large business customer are much more likely to receive skills and innovation support, mainly focussed on ‘sharing workforce expertise and time’. This group is also most likely to report ‘increased turnover’ as the most common benefit of their subsequent innovation (other size groups reported ‘improved reputation, credibility and profile’). Those supplying to same size or smaller customers are much more likely to agree to payment terms in advance or on delivery, and more likely to be paid on time, compared to those supplying to larger customers, the latter of which, are also more likely to hold at least one certified standard, tend to hold more of them, and pay much more for the privilege. - Length of time of business operation (e.g. whether a recent start-up)

Unsurprisingly, start-ups are more likely to receive skills and innovation support from customers, compared to more established businesses. Start-ups are also more likely to receive innovation support related to processes, as well as products. Across the spectrum of business life-cycles, the most widely reported innovation benefit is ‘improved reputation, credibility and profile’. However, for start-ups, ‘opportunities for other collaboration’ is also seen as a particularly important benefit as they seek to grow. Compared to more established businesses, start-ups are more likely to negotiate payment in advance or on delivery, and less likely to agree payment terms of later than 60 days. They are also more likely to be paid on time. They tend to hold fewer standards and pay less for them, compared to more established suppliers.

Around three quarters (77%) of FSB small businesses say they supply to business customers across a range of different sizes, and across both the private and public sectors. FSB research has highlighted some key areas where supply chain policies of Government and, in particular, larger business customers could have a major impact, either positive or negative depending on how they are implemented.

This report examines what more can be done to boost productivity through supply chains, by increasing practices that support innovation and skills development in smaller suppliers. It also explores what more can be done to improve supply chain resilience (by tackling poor payment practice) and efficiency (particularly by improving the UK’s standards regime).

Boosting productivity by increasing innovation and skills

It is widely acknowledged that innovation and skills are drivers of productivity. FSB’s research shows that when help to innovate and develop skills is cascaded down the supply chain, smaller suppliers benefit significantly. This benefits the UK economy as a whole.

FSB research suggests that almost a third (30%) of smaller suppliers receive help to innovate from their business or public sector customers. Of these, the most commonly reported types of support include the sharing of workforce expertise and time (33%), collaboration in design (23%), mentoring and advice (20%), and market research (15%). Of those that have received help to innovate from customers, the vast majority (83%) say it had a positive impact on their business.

Support for skills is less widely reported by smaller suppliers, compared to support for innovation. Only one in ten (12%) small suppliers say their business or public sector customers have provided any skills or workforce development support in the previous two years. Of those that have, the most commonly reported types of support relate to training and skills development (42%), discounted training courses (32%) and access to free resources (27%).

Of those small suppliers that have been offered, and accepted, skills and workforce development support from customers, more than half (55%) say it has improved the skills, knowledge and expertise in their business. This clearly indicates an area on which policy makers can build in the future.

Many larger business customers are well-placed to understand and work with their supply chains to identify and address any skills or operational shortfalls that might threaten to disrupt the service they receive. Larger companies should recognise the mutual benefits of supporting their smaller suppliers, sharing their knowledge and expertise to address skills shortages and boost innovation. This is a win-win scenario, with benefits inevitably flowing back up the supply chain and to the economy as a whole.

Increasing financial strength and resilience

Despite some recent improvements, many smaller suppliers continue to face challenges related to late payments, lengthy payment periods of more than 60 days, and other inequitable contract terms forced upon them by their larger business customers. At a time of rising costs associated with operating a business in the UK[2], these additional pressures further increase the risk of running a small firm.

FSB research suggests that a significant minority of smaller businesses (17%) are paid more than 60 days after providing an invoice. This data is remarkably similar to the 16 per cent figure obtained by Government from firms that are required to report their payment practices.3

FSB research has also revealed that payment terms are worsening for smaller suppliers. More than a third (37%) of FSB smaller suppliers say that their payment terms have increased over the last two years, while less than one in twenty (4%) have experienced an improvement in their payment terms. Previous FSB research showed that almost one in five (17%) FSB small businesses said they had experienced supply chain bullying[3] in the previous two years, including retrospective discounting.[4]

In some cases, there is a clear power imbalance between smaller suppliers and the larger business and public sector customers they serve. Nearly a quarter (24%) of FSB smaller suppliers say they are unable to influence the terms of their contracts with customers. Furthermore, a sixth (17%) say they are unable to challenge their customers.

In this context, it must be noted that ‘customers failing to pay’ is the top risk for FSB smaller suppliers (see below). Small firms must be empowered to understand and mitigate a broad range of risks, particularly those that threaten the quality of service they provide to their customers. However, a lack of resilience planning by many smaller businesses means that their supply chains remain vulnerable to potentially substantial disruption. This increases the risk of lower productivity growth, higher costs, customer complaints, lost revenue, and reputational damage. The most commonly reported risks to supply chains by FSB smaller suppliers are:

- Customers failing to pay for services / goods provided (51%)

- Losing key members of staff (37%)

- Suppliers unable to supply (30%)

- IT problems (29%)

Increasing efficiency and reducing costs

Increasing competition within supply chains, and reducing unnecessary costs, will increase the competitiveness of UK firms and supply chains more generally. Improving the UK’s complex standards regime would provide one of the greatest opportunity areas in this regard. Standards are too often designed ineffectively in ways that damage small businesses and fail to meet stated objectives.

FSB research suggest that two thirds (66%) of smaller suppliers hold at least one kind of verified standard, e.g. a quality management standard like ISO9001 (see ANNEX 2). On average, smaller businesses hold four separate certified standards, with that number increasing with the size of business. There is also a sectoral variation, with businesses in the construction sector holding more standards on average than those in others sectors like manufacturing and wholesale/retail. Across all sectors, the average cost of these standards for smaller suppliers is more than £2,800 a year.

Most (75%) smaller suppliers hold standards simply because they are required to by their customers or insurance companies. However, certified standards can bring benefits to some smaller businesses. Of those that do hold standards, around two fifths believe they help to differentiate themselves from competitors (43%) or help to improve the quality of their service or products (39%). Previous FSB research showed that the majority (70%) of small businesses recognise areas where some regulation, including certified standards and products standards, can have a positive impact.[5]

However, it is also clear that standards currently do not fulfil their potential and can create net costs to smaller businesses. This is usually due to their complexity, the time and costs required (often involving consultants), or their lack of interoperability, despite many standards covering the same areas.

Government and the standards industry must take action to reduce unnecessary costs to UK businesses and help ensure that smaller suppliers have a standards regime that enables them to play their full role in increasing productivity, employment and consumer benefit. This includes the removal of duplication within many standards requirements.

Public procurement

Government has an opportunity to lead by example on supply chain best practice, in relation to both the proportion of smaller suppliers with which it directly and indirectly contracts, and in the way it treats these businesses. However, the public sector is yet to set itself apart in this regard, and must do more to widen its use of smaller suppliers if it is to achieve its target of 33 per cent of public procurement with smaller businesses by 2022.

One of the areas where the public sector appears to do relatively well, compared to the private sector, is in collaborating with their suppliers on the design of products and services (28% compared to 23% population average) and also providing their suppliers with mentoring and advice (25% compared to 20% population average).

The public sector should also be recognised for its attempt to drive down payment terms. Those supplying to national or local government projects are more likely to agree payment in advance or on delivery (30% compared to 26% population average), or within 8-30 days (54% compared to 45% population average).

However, FSB data on late payments suggests that the public sector subsequently struggles to honour these terms. Almost one in five (17%) smaller suppliers to the public sector say they are paid late more than half the time (compared to 14% population average).

In terms of the innovation support provided to smaller suppliers by their customers, and the success this brings, the public sector appears to be relatively effective in particular areas. For example, of the smaller suppliers that are provided with innovation support by their customers, those supplying to the public sector were more likely to say this support improved their reputation, credibility and profile (43% compared to 39% population average), provided opportunities for collaboration (32% compared to 26% population average), and provided access to more customers (32% compared to 25% population average).

There is a noticeable difference in the prevalence of verified standards among those businesses that supply to the public sector (including public sector infrastructure projects) compared to the wider supplier population. Three-quarters (75%) of smaller firms that supply to the public sector hold at least one verified standard. This is nine per cent higher than the proportion across all businesses in supply-chains (66%).

[1] This research looked at business size groups of 0 employees (sole traders), 1-10 employees (microbusinesses), 11-20 employees, and 21+ employees

[2] FSB, Voice of Small Business Index, Q1 2018, 3 Gov UK data, available at https://check-payment-practices service gov uk/export

[3] For example, large firms using the disparity of power in business relationships to squeeze their suppliers, delaying payments to improve their own cash flow

[4] FSB, Time to Act: The economic impact of poor payment practice, 2016.

[5] FSB, Regulation Returned: What small firms want from Brexit, 2017

Recommendations

Download the full report

Click below to download the full report